We’re thrilled to reveal the cover and share an excerpt from Maria Dahvana Headley’s upcoming novel The Mere Wife. A modern retelling of the literary classic Beowulf, The Mere Wife is set in American suburbia as two mothers—a housewife and a battle-hardened veteran—fight to protect those they love.

The Mere Wife publishes July 18th with Farrar, Straus & Giroux. From the catalog copy:

From the perspective of those who live in Herot Hall, the suburb is a paradise. Picket fences divide buildings—high and gabled—and the community is entirely self-sustaining. Each house has its own fireplace, each fireplace is fitted with a container of lighter fluid, and outside—in lawns and on playgrounds—wildflowers seed themselves in neat rows. But for those who live surreptitiously along Herot Hall’s periphery, the subdivision is a fortress guarded by an intense network of gates, surveillance cameras, and motion-activated lights.

For Willa, the wife of Roger Herot (heir of Herot Hall), life moves at a charmingly slow pace. She flits between mommy groups, playdates, cocktail hour, and dinner parties, always with her son, Dylan, in tow. Meanwhile, in a cave in the mountains just beyond the limits of Herot Hall lives Gren, short for Grendel, as well as his mother, Dana, a former soldier who gave birth as if by chance. Dana didn’t want Gren, didn’t plan Gren, and doesn’t know how she got Gren, but when she returned from war, there he was. When Gren, unaware of the borders erected to keep him at bay, ventures into Herot Hall and runs off with Dylan, Dana’s and Willa’s worlds collide.

From author Maria Dahvana Headley:

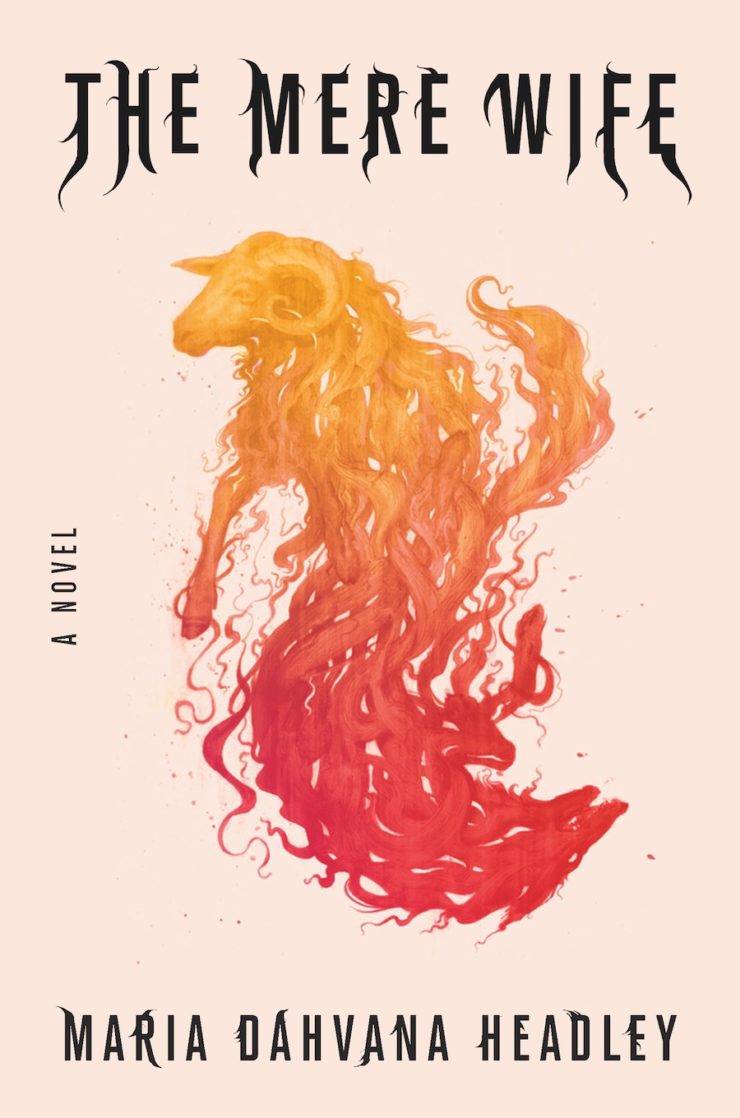

I wasn’t familiar with the art of Miranda Meeks before this cover, but now that I am, I can easily say that she could illustrate anything I’ve written. In fact, she sort of already has—her portfolio is full of things like lungs full of birds, and owl-headed women, both of which concepts show up in my young adult novels, Magonia and Aerie.

The Miranda Meeks piece that Keith Hayes chose for The Mere Wife reminds me, appropriately, of something from an illuminated manuscript. It’s furious without being terrifically graphic, which I appreciate. And it’s wildness versus domestication, blood versus fleece, but not really even versus—it’s more a virtual representation of the way that these things are always inextricably braided together. The art was re-colored for this cover, into more of a blaze of neon Day-Glo, to let us know this isn’t old blood we’re talking about, but fresh. And the gloriously furred and fanged text for both my name and the title, is just… well, I think, having seen it, I’ve always wanted my name to have claws.

The novel is definitely violent, because it’s based on Beowulf! But it’s also full of poetry, because, um, it’s based on Beowulf! I think this piece of art manages to encompass both things, the wrath of the book and the fluidity of it as well. I mean, this is a book full of choral speaking. There’s a murder of matriarchs (can I just use that as the collective noun for this version?—I don’t usually feel that way about matriarchs, but these are pretty murderous) who have collective POV, and function as the soldiers of suburbia. There are collective chapters from the POV of the natural world as well—the mountain, the mere, the animals and ghosts of the place, as well as a chapter from the POV of a pack of police dogs. The book often plays with mirrors: there are two young boys, one living inside the mountain, one in Herot Hall, and two main female characters, one the war veteran Dana Mills, who is the Grendel’s mother character, and the other the very privileged former actress Willa Herot, who is the Hrothgar’s wife equivalent.

The nature of the book is that all these things are tangled together, despite the notion of separation between them. The gated community still has its back open to the mountain. The boy from outside hears a piano lesson echoing up from the home of the boy raised indoors. And into all of this comes Ben Woolf, a police officer who believes he’s the hero Herot needs. The nature of the illustration speaks to that as well, in my opinion—there’s something of the classical hero’s spoils in what we’re looking at on this cover. Golden fleeces and monstrous canines. In the end, The Mere Wife is about the ways that Others are created, and the way that our society is mercilessly divided into poisoned binaries. In the source, aeglaeca, the word used for Beowulf and Grendel, and even for Grendel’s mother, are the same word (in her case, the feminine equivalent). The word doesn’t mean hero, nor does it mean monster. It probably means fierce fighter.

So, this cover, to my eye? Is an act of accurate translation, ram and wolf, transforming, entwining, finally being shown as two sides of the same entity.

From artist Miranda Meeks:

The creation of this cover is built upon themes of dualism and polarity. It conveys that life isn’t black and white; it’s messy, and broken, and the gray area is a lot more encompassing than people initially assume. The human brain relishes in categorizing people into two different groups: there are only good people or bad people. This illustration suggests an alternative perspective, in that everyone has a delicate balance of good and bad inside them, and the two sides aren’t polarized either. The ram and wolf symbolize the classic struggle of predator versus prey, but instead of both sides directly opposing each other, they are woven and entwined together, until it’s difficult to see where the two sides meet in the middle. There is both intimacy and power behind this delicate balance of light and darkness. It is important to recognize this coexistence within ourselves so that we might further develop deep and personal relationships with those we love.

Sean McDonald, publisher of MCD/FSG Books:

Maria gave the cover designers a lot to work with—The Mere Wife is full of myths and monsters, blood and fangs and fur and… one perfectly dystopic American suburb. And as with all great covers, the designers distilled into it an utterly unexpected but instantly undeniable package. Who would put a crazy neon ram’s-head-wolf-thing on the cover of a book—and then, naturally, have the type sprout fangs and fur too!—and think it would look anything but bonkers? And yet it’s perfect, elegant even, in its way—but mostly it’s beautiful and rich and weird and modern and mythic and utterly magnetic and irresistible, just like the book Maria wrote.

Buy the Book

Listen. Long after the end of everything is supposed to have occurred, long after apocalypses have been calculated by cults and calendared by computers, long after the world has ceased believing in miracles, there’s a baby born inside a mountain.

Earth’s a thieved place. Everything living needs somewhere to be.

There’s a howl and then a whistle, and then a roar. Wind shrieks around the tops of trees, and sun melts the glacier at the top of the peak. Even stars sing. Boulders avalanche and snow drifts, ice moans.

No one needs to see us for us to exist. No one needs to love us for us to exist. The sky is filled with light.

The world is full of wonders.

We’re the wilderness, the hidden river, and the stone caves. We’re the snakes and songbirds, the storm water, the brightness beneath the darkest pools. We’re an old thing made of everything else, and we’ve been waiting here a long time.

We rose up from an inland sea, and now, half beneath the mountain, half outside it, is the last of that sea, a mere. In our soil there are tree fossils, the remains of a forest, dating from the greening of the world. They used to be a canopy; now they spread their stone fingers underground. Deep inside the mountain, there’s a cave full of old bones. There was once a tremendous skeleton here, rib cage curving the wall, tail twisting across the floor. Later, the cave was widened and pushed, tiled, tracked, and beamed to house a train station. The bones were pried out and taken to a museum, reassembled into a hanging body.

The station was a showpiece before it wasn’t. The train it housed went back and forth to the city, cocktail cars, leather seats. The cave’s walls are crumbling now, and on top of the stone the tiles are cracking, but the station remains: ticket booth, wooden benches, newspaper racks, china teacups, stained-glass windows facing outward into earthworms, and crystal chandeliers draped in cobwebs. There are drinking fountains tapping the spring that feeds the mountain, and there’s a wishing pool covered in dust. No train’s been through our territory in almost a hundred years. Both sides of the tunnel are covered with metal doors and soil, but the gilded chamber remains, water pouring over the tracks. Fish swim in the rail river and creatures move up and down over the mosaics and destination signs.

We wait, and one day our waiting is over.

A panel in the ceiling moves out of position, and a woman drops through the gap at the end of an arch, falling a couple of feet to the floor, panting.

She’s bone-thin but for her belly. She staggers, leans against our wall, and looks up at our ceiling, breathing carefully.

There’s a blurry streak of light, coming from the old skylight, a portal to the world outside. The world inside consists only of this woman, dressed in stained camo, a tank top, rope-belted fatigues, combat boots, a patch over one eye, hair tied back in a piece of cloth. Her face is scarred with a complicated pink line. On her back, there are two guns and a pack of provisions.

She eases herself down to the tiles. She calls, to any god, to all of them.

She calls to us.

Excerpted from The Mere Wife, copyright © 2018 by Maria Dahvana Headley